There are “serious challenges ahead” for the fitness market even as gyms reopen.

By Benedict Smith ABC News

As 49 states and D.C. take the first steps in releasing their economies from coronavirus restrictions – with Connecticut set to follow suit on Wednesday – the fitness industry is adjusting to life post-lockdown.

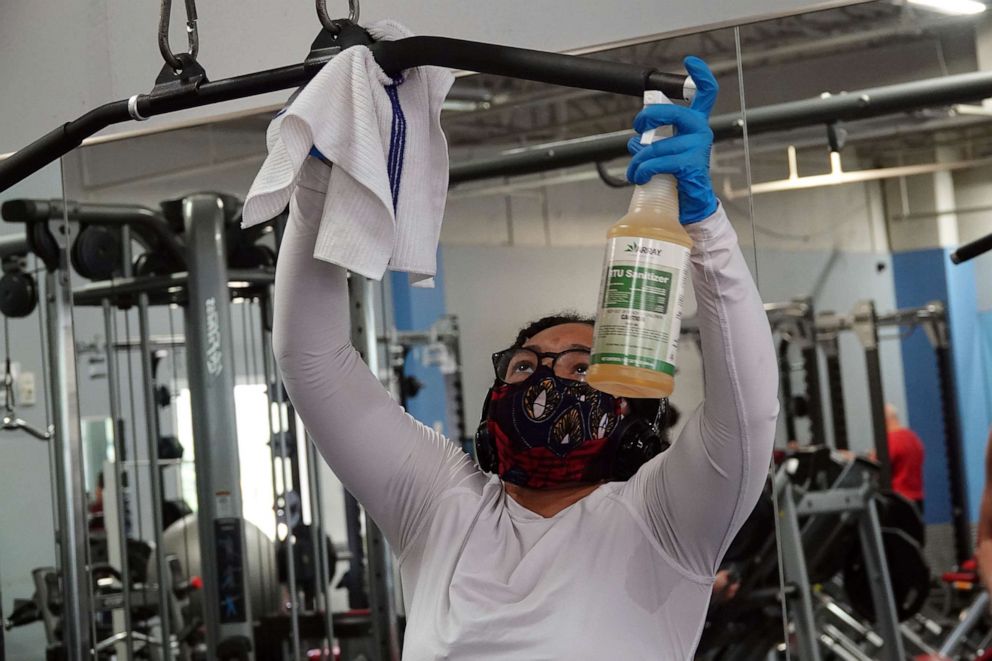

It’s certainly not business as usual in a world of social distancing and strict sanitation protocol. In some cases, it’s not even business at all: gyms are still closed across much of the U.S.

But as the economy slowly emerges after weeks of shutdown, there are “serious challenges ahead” for the fitness market, according to Beth McGroarty of The Global Wellness Institute.

Health clubs have been expanding into spaces “once occupied by department and smaller stores at shopping centers and on city streets,” explained McGroarty. The widespread lockdown in March, however, decimated the revenue of gym owners and left them struggling to pay rent on their large retail locations.

This financial frailty meant a number of fitness chains continued charging membership fees after shutting their facilities.

“Not a great way to build future trust,” said McGroarty, “if you think you have a future.”

But it’s not just consumers who have suffered a crisis of confidence in the industry. COVID-19 has exposed the fault lines in the relationships of multiple stakeholders from gym owners to their employees to the government.

On April 16, President Trump revealed that fitness centers would be included in the first stage of federal guidelines for lifting lockdown across America.

The move was supported by the International Health, Racquet and Sportsclub Association (IHRSA), which calculates these centers had been hemorrhaging $700 million per week at the height of movement restrictions — more than the rest of the global market combined.

Georgia Governor Brian Kemp authorized gyms to reopen eight days after the president’s announcement, by which time IHRSA believes the U.S. fitness industry had taken a hit of around $2.8 billion.

Utah, Wyoming, Oklahoma, North Dakota, and all but a handful of counties in Tennessee and Iowa, followed Georgia’s lead on May 1. Currently, around 20 states have allowed gyms to reopen.

But despite sanctions at both the state and the federal level — along with the prospect of easing their financial woes — some fitness chains appear cautious. COVID-19 has hit the U.S. harder than any other country, infecting 1.4 million people (compared to 4.7 million globally) and killing around 89,564.

Planet Fitness is enacting a “thoughtful and phased reopening approach,” according to spokeswoman McCall Gosselin. The gym giant’s first quarter fiscal results show net income has plummeted by 67%.

Its reopening strategy began on May 1, when just three clubs across Georgia and Utah resumed operations.

By May 13 — by which point Arkansas, Missouri, Alaska, Mississippi, Alabama, and Arizona had also relaxed gym restrictions — only 50 Planet Fitness locations had opened their doors.

A very different story is playing out in Virginia, where health club owner Merrill C. Hall has accused Governor Ralph Northam of “literally destroy[ing]my business” by keeping lockdown measures in place.

Gyms have been closed since Northam issued Executive Order 53 on March 23, shutting all recreational and entertainment businesses in the state. It was meant to expire after a month which led to Hall launching a lawsuit to challenge the order after it was extended to May 8.

Hall said time is of the essence, and calculates that the rent on his nine locations comes to around $750,000 per month.

His attorneys argue that Executive Order 53 is an overreach of Northam’s authority and “trample[s]upon fundamental rights and laws” of the Virginia Constitution. The case is being taken before the Virginia Supreme Court after a Circuit Court judge recently denied the challenge.

Governor Northam did not respond to requests for comment.

For now, gyms remain closed as Virginia moves towards the first phase of reopening its economy, though outdoor fitness classes will be permitted in certain areas of the state.

Elsewhere, fitness chains have found themselves firmly on the defensive against government pressure. When a number of centers shut their doors while continuing to charge membership fees, they opened the door to social media scorn and a political backlash.

One such organization was Town Sports International (TSI), which upheld membership charges after its facilities shut on March 16. CEO Patrick Walsh initially attempted to reassure customers that their concerns would be addressed “once we’re up and functionally running.”

A multi-state coalition was formed after a public outcry, made up of the Attorneys General of New York, Washington, D.C. and Pennsylvania. In an open letter to TSI , they threatened to “take whatever steps are necessary to protect our citizens” if multiple policy changes didn’t take place.

The company agreed to honor cancellation fees submitted by the end of April, issue credits for membership charges, and resolve individual complaints filed with the Attorneys General.

The Town Sports Team had earlier announced that membership charges would be frozen “at no cost to you” across all states as of April 8.

But some customers aren’t satisfied with TSI’s concessions. One member, Mary Namorato, is proceeding with a class action complaint that she filed against the gym giant in late March.

Her attorney, David Gottlieb of Wigdor LLP, downplayed TSI’s membership freeze as a “transparent attempt to try and appear like it is doing the right thing, when it is actually doing the opposite.”

“We believe hundreds of thousands of gym members are on a first of the month billing cycle, and by waiting until after [April 1] to make this change allowed them to collect tens of millions of dollars in additional membership fees,” he explained to ABC News.

TSI was approached for comment but did not respond.

Membership charges have proven a particularly contentious, as well as litigious, issue across the U.S.

At least six major fitness chains are facing legal challenges from customers after allegedly charging fees during lockdown. The law firm Bursor & Fisher, P.A. is acting for plaintiffs against three of these companies: 24 Hour Fitness, Blink Fitness, and Fit Republic.

In one notable case, LA Fitness is being sued by a member who had belonged to the club for 14 years.

Coronavirus class actions, however, have not just been confined to America — and they haven’t just been brought by disgruntled members.

During the lockdown period, most fitness chains have furloughed their employees, while retaining a skeleton staff to deal with customer service issues. But Steve Nash Fitness World (SNFW) — which claims to be the largest fitness provider in British Columbia — took more drastic steps after closing.

It said in a statement that it decided “to let go of our valued team members,” on account of “an organizational restructuring during these tough and unprecedented times.”

The move prompted Brenie Matute — an instructor at the gym since 2017 — to bring a class action complaint against her former employers. She claims over 1,200 employees have been fired, and that SNFW provided no notice of termination.

According to a March 17 company statement, “team members will be paid to lessen the financial burden” over “the first two weeks of this initial closure.” Matute’s lawyers argue former staff are entitled to individual compensation (2-8 weeks’ pay) and group compensation (16 weeks’ pay) in lieu of notice.

Ex-employees also claim that the mass terminations derailed an internal complaint of bullying and harassment at SNFW. They’ve started a petition, which has garnered over 2,000 signatures, calling for the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal to investigate the organization.

“Together we can stand and make a change for ourselves and the future of the fitness industry,” it concludes.

SNFW did not respond to requests for comment.

Despite the numerous fractured relationships in the fitness industry, Beth McGroarty remains optimistic about its future.

Digital fitness classes have proved incredibly popular in the era of self-isolation, and show the public’s attachment to their local gym as a place of community.

McGroarty argues that the path forward for health clubs is a hybrid model – balancing online classes with selective visits to the gym – to provide this “human connection” in “our age of loneliness and disconnection.”

But now, she says, it’s up to businesses to get that model “safe and right.”