By Max De Haldevang and Nacha Cattan

Mexico’s new finance chief has spent decades at Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador’s side. That experience will come in handy as he takes on his biggest challenge: trying to shape economic policy in an administration tightly run by the nationalist president.

Rogelio Ramirez de la O, who last week was nominated as Mexico’s finance minister, will begin what is traditionally the country’s most influential cabinet role with the goal of obtaining a level of independence his predecessors didn’t enjoy under Lopez Obrador.

An early test in the relationship between the president known as AMLO and his long-time adviser will focus on the budget: The new minister, who takes office next month, wants to speed up growth via additional debt-fueled public spending, according to people with knowledge of his thinking.

That would be a significant shift for a president who has made austerity a pillar of his government. AMLO has stuck to his pledge not to take on new debt or give sizable economic stimulus even during the Covid pandemic, and Mexico ended 2020 as one of the few countries in the world with a primary surplus.

The president repeated his austerity vow after announcing the arrival of Ramirez de la O on June 9, saying he won’t raise taxes and will keep energy prices capped. Threading the needle between those diverging policy preferences will depend a lot on the relationship between the two men, who have known each other since 1997.

“There are things that I believe that Rogelio doesn’t share with the president: for example, I would think that in the pandemic Rogelio would have advised to do a fiscal stimulus program to tackle the pandemic,” said Gabriel Casillas, the chief economist at Grupo Financiero Banorte. “Having seen the pandemic and still with the problem of growth in Mexico, I think that’s why AMLO asked Rogelio to become Finance Minister — because he wants help and he’s a seasoned economist.”

The peso lost about 1.5% to the dollar since the announcement, with stocks slightly up on average.

Lost Influence

In the past decades, Mexico’s finance ministers wielded significant power to shape the country’s political economy, at times even overshadowing the presidency. That changed with the arrival of Lopez Obrador in late 2018, as the president slashed budgets and canceled major infrastructure projects while plowing the little money available into social programs and struggling state energy firms.

As a result, AMLO’s first two finance ministers made little impact on policy. The first incumbent, Carlos Urzua, another old Lopez Obrador ally, resigned just seven months into the job with a letter suggesting policy hadn’t been “based on evidence,” as the economy headed into recession before the pandemic.

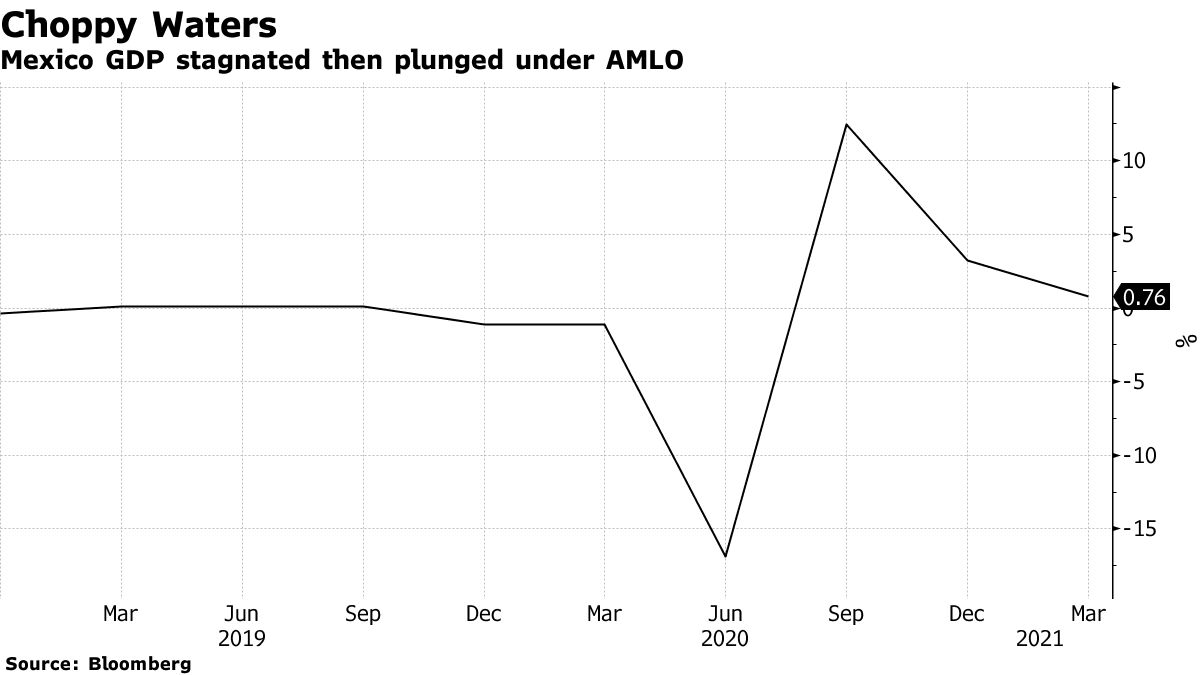

Outgoing minister Arturo Herrera was seen as a loyal executor of the president’s ideas, keeping spending tight as gross domestic product plunged 8.2% in 2020, the most in almost a century. He was nominated to head the country’s central bank as part of last week’s changes, and will help oversee an economy that is now rebounding faster than expected as strong U.S. demand propels the manufacturing sector.

Ramirez, 72, only took the job on the condition that he would be given more autonomy and greater control over spending on state oil giant Petroleos Mexicanos and the country’s utility, a person familiar with the talks told Bloomberg News. A second source confirmed that Ramirez pushed for control over energy spending, an area of influence for the Finance Ministry in previous administrations.

Other changes are expected to the Finance Ministry leadership, according to the people with knowledge of the matter, including the appointment of a new deputy minister likely to be an official currently holding another position in government.

Right Timing?

Many economists believe Ramirez, who rose to fame for correctly predicting the sharp currency devaluation that triggered what was known as the 1994 Tequila Crisis, could obtain extra revenue through efforts to broaden government tax collection. But convincing the president to take a more debt-financed, Keynesian approach to economic policy would be a tall order.

“Considering that Rogelio has been an adviser to AMLO for a long time and he hasn’t manged to change this, I see a low probability that he will abandon the idea,” said Janneth Quiroz Zamora, vice-president for economic research at Monex Casa de Bolsa.

The president’s spokesman Jesus Ramirez poured cold water on the idea that the government could take on more debt. The president’s policy “has been to not spend more than what the government earns — and it is proposed to continue like that,” he told Bloomberg News. “For that reason, taking on more debt or increasing the budget deficit is not being thought about. Tax income has increased this year and spending will grow proportionately.”

Yet, even if he can’t convince AMLO to borrow more, one thing that favors the incoming minister in his quest for more autonomy is timing.

After AMLO’s Morena party lost its lower-house majority in this month’s midterms, the president may need to put power back into the hands of a finance minister who can handle the wheeling and dealing needed to pass the federal budget in the fall, said Marco Oviedo, chief Latin America economist at Barclays Plc.

“In Mexico, the finance minister used to be a super minister and that ended with Lopez Obrador. Now, with congress divided, you need that back,” Oviedo said.