By ANDREW DALTON

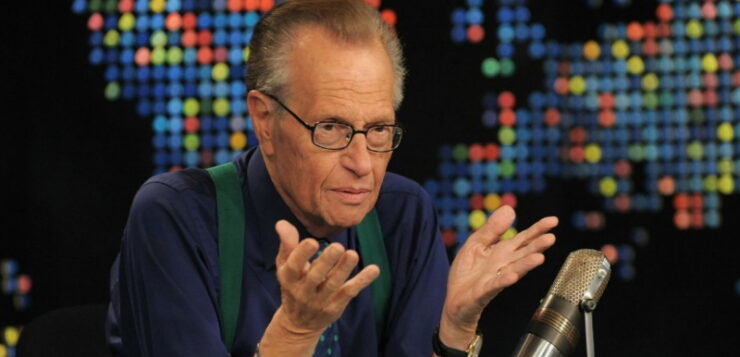

LOS ANGELES (AP) — Larry King, the suspenders-sporting everyman whose broadcast interviews with world leaders, movie stars and ordinary Joes helped define American conversation for a half-century, died Saturday. He was 87.

King died at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, his production company, Ora Media, tweeted. No cause of death was given, but a spokesperson said Jan. 4 that King had COVID-19, had received supplemental oxygen and had been moved out of intensive care. His son Chance Armstrong also confirmed King’s death, CNN reported.

A longtime nationally syndicated radio host, from 1985 through 2010 he was a nightly fixture on CNN, where he won many honors, including two Peabody awards.

With his celebrity interviews, political debates and topical discussions, King wasn’t just an enduring on-air personality. He also set himself apart with the curiosity he brought to every interview, whether questioning the assault victim known as the Central Park jogger or billionaire industrialist Ross Perot, who in 1992 rocked the presidential contest by announcing his candidacy on King’s show.

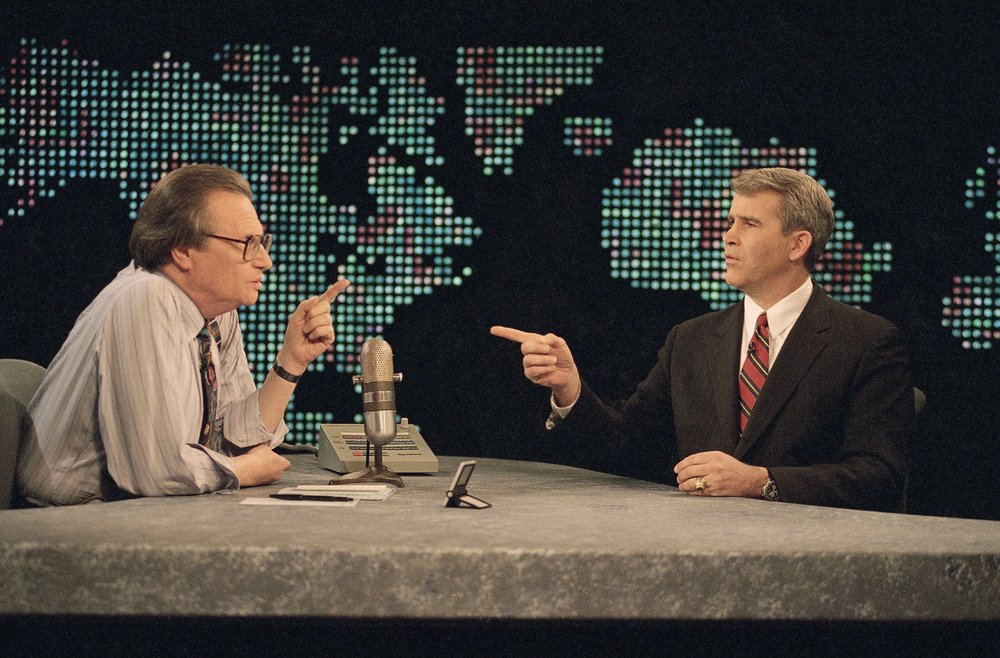

In its early years, “Larry King Live” was based in Washington, which gave the show an air of gravitas. Likewise King. He was the plainspoken go-between through whom Beltway bigwigs could reach their public, and they did, earning the show prestige as a place where things happened, where news was made.

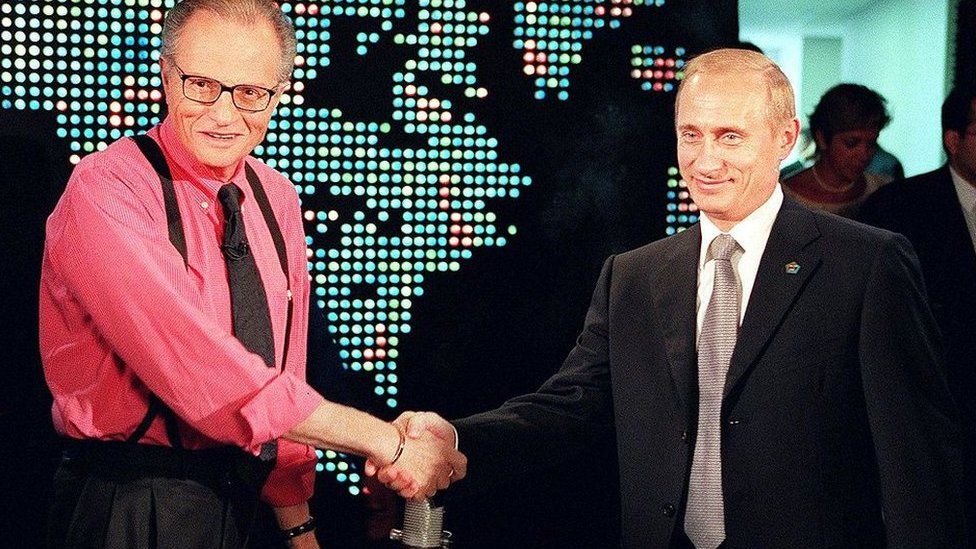

King conducted an estimated 50,000 on-air interviews. In 1995 he presided over a Middle East peace summit with PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat, King Hussein of Jordan and Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin. He welcomed everyone from the Dalai Lama to Elizabeth Taylor, from Mikhail Gorbachev to Barack Obama, Bill Gates to Lady Gaga.

Especially after he relocated to Los Angeles, his shows were frequently in the thick of breaking celebrity news, including Paris Hilton talking about her stint in jail in 2007 and Michael Jackson’s friends and family members talking about his death in 2009.

King boasted of never overpreparing for an interview. His nonconfrontational style relaxed his guests and made him readily relatable to his audience.

“I don’t pretend to know it all,” he said in a 1995 Associated Press interview. “Not, `What about Geneva or Cuba?′ I ask, `Mr. President, what don’t you like about this job?′ Or `What’s the biggest mistake you made?′ That’s fascinating.”

At a time when CNN as the lone player in cable news was deemed politically neutral, and King was the essence of its middle-of-the-road stance, political figures and people at the center of controversies would seek out his show.

And he was known for getting guests who were notoriously elusive. Frank Sinatra, who rarely gave interviews and often lashed out at reporters, spoke to King in 1988 in what would be the singer’s last major TV appearance. Sinatra was an old friend of King’s and acted accordingly.

“Why are you here?” King asks. Sinatra responds, “Because you asked me to come and I hadn’t seen you in a long time to begin with, I thought we ought to get together and chat, just talk about a lot of things.”

King had never met Marlon Brando, who was even tougher to get and tougher to interview, when the acting giant asked to appear on King’s show in 1994. The two hit it off so famously they ended their 90-minute talk with a song and an on-the-mouth kiss, an image that was all over media in subsequent weeks.

After a gala week marking his 25th anniversary in June 2010, King abruptly announced he was retiring from his show, telling viewers, “It’s time to hang up my nightly suspenders.” Named as his successor in the time slot: British journalist and TV personality Piers Morgan.

By King’s departure that December, suspicion had grown that he had waited a little too long to hang up those suspenders. Once the leader in cable TV news, he ranked third in his time slot with less than half the nightly audience his peak year, 1998, when “Larry King Live” drew 1.64 million viewers.

His wide-eyed, regular-guy approach to interviewing by then felt dated in an era of edgy, pushy or loaded questioning by other hosts.

Meanwhile, occasional flubs had made him seem out of touch, or worse. A prime example from 2007 found King asking Jerry Seinfeld if he had voluntarily left his sitcom or been canceled by his network, NBC.

“I was the No. 1 show in television, Larry,” replied Seinfeld with a flabbergasted look. “Do you know who I am?”

Always a workaholic, King would be back doing specials for CNN within a few months of performing his nightly duties.

He found a new sort of celebrity as a plainspoken natural on Twitter when the platform emerged, winning over more than 2 million followers who simultaneously mocked and loved him for his esoteric style.

“I’ve never been in a canoe. #Itsmy2cents,” he said in a typical tweet in 2015.

His Twitter account was essentially a revival of a USA Today column he wrote for two decades full of one-off, disjointed thoughts. Norm Macdonald delivered a parody version of the column when he played King on “Saturday Night Live,” with deadpan lines like, “The more I think about it, the more I appreciate the equator.”

King was constantly parodied, often through old-age jokes on late-night talk shows from hosts including David Letterman and Conan O’Brien, often appearing with the latter to get in on the roasting himself.

King came by his voracious but no-frills manner honestly.

He was born Lawrence Harvey Zeiger in 1933, a son of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe who ran a bar and grill in Brooklyn. But after his father’s death when Larry was a boy, he faced a troubled, sometimes destitute youth.

A fan of such radio stars as Arthur Godfrey and comedians Bob & Ray, King on reaching adulthood set his sights on a broadcasting career. With word that Miami was a good place to break in, he headed south in 1957 and landed a job sweeping floors at a tiny AM station. When a deejay abruptly quit, King was put on the air — and was handed his new surname by the station manager, who thought Zeiger “too Jewish.”

A year later he moved to a larger station, where his duties were expanded from the usual patter to serving as host of a daily interview show that aired from a local restaurant. He quickly proved equally adept at talking to the waitresses, and the celebrities who began dropping by.

By the early 1960s King had gone to yet a larger Miami station, scored a newspaper column and become a local celebrity himself.

At the same time, he fell victim to living large.

“It was important to me to come across as a ‘big man,”’ he wrote in his autobiography, which meant “I made a lot of money and spread it around lavishly.”

He accumulated debts and his first broken marriages (he was married eight times to seven women). He gambled, borrowed wildly and failed to pay his taxes. He also became involved with a shady financier in a scheme to bankroll an investigation of President John Kennedy’s assassination. But when King skimmed some of the cash to pay his overdue taxes, his partner sued him for grand larceny in 1971. The charges were dropped, but King’s reputation appeared ruined.

King lost his radio show and, for several years, struggled to find work. But by 1975 the scandal had largely blown over and a Miami station gave him another chance. Regaining his local popularity, King was signed in 1978 to host radio’s first nationwide call-in show.

Originating from Washington on the Mutual network, “The Larry King Show” was eventually heard on more than 300 stations and made King a national phenomenon.

A few years later, CNN founder Ted Turner offered King a slot on his young network. “Larry King Live” debuted on June 1, 1985, and became CNN’s highest-rated program. King’s beginning salary of $100,000 a year eventually grew to more than $7 million.

A three-packs-a-day cigarette habit led to a heart attack in 1987, but King’s quintuple-bypass surgery didn’t slow him down.

Meanwhile, he continued to prove that, in his words, “I’m not good at marriage, but I’m a great boyfriend.”

He was just 18 when he married high school girlfriend Freda Miller, in 1952. The marriage lasted less than a year. In subsequent decades he would marry Annette Kay, Alene Akins (twice), Mickey Sutfin, Sharon Lepore and Julie Alexander.

In 1997, he wed Shawn Southwick, a country singer and actress 26 years his junior. They would file for divorce in 2010, rescind the filing, then file for divorce again in 2019.

The couple had two sons — King’s fourth and fifth kids, Chance, born in 1999, and Cannon Edward, born in 2000. In 2020, King lost his two oldest children, Andy King and Chaia King, who died of unrelated health problems within weeks of each other.

He had many other medical issues in recent decades, including more heart attacks and diagnoses of type 2 diabetes and lung cancer.

Through his setbacks he continued to work into his late 80s, taking on online talk shows and infomercials as his appearances on CNN grew fewer.

“Work,” King once said. “It’s the easiest thing I do.”

Funeral arrangements and a memorial service will be announced later in coordination with the King family, “who ask for their privacy at this time,” according to the tweet from Ora Media.

___

Former AP Television Writer Frazier Moore contributed biographical material to this report.